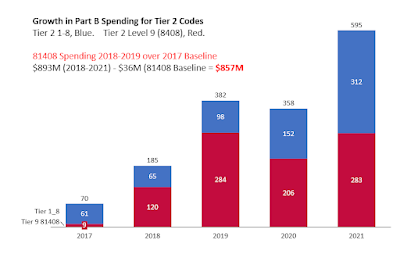

For several years, since 2018, there has been a shocking growth in the use of Tier 2 codes in Medicare Part B, with a significant portion of labs using these codes in high amounts being indicted by Department of Justice.

- See big Department of Justice press releases around September 2019 as Operation Double Helix (here) and again in August 2022 (entry point here).

You can just use the "fingerprint" pattern of super high Tier 2 code billing (by indicted labs) as a "magnet" to look for similar lab billing patterns.

The billing patterns are lab operations dominated by all the Tier 2 codes, and often only the Tier 2 codes. These payment patterns, which are over the top unbelievable, are almost entirely in Novitas and FCSO MAC regions. Since it is impossible imagine that one Medicare patient needs all of the Tier 2 codes on one day, let alone 1000 patients in a row, I call these "Highly Unlikely Codes."

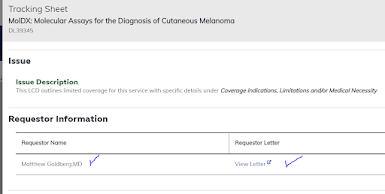

On a smaller scale (topping out at $200M rather than $280M) is labs dominantly billing just for 87798, "other pathogen, PCR." At least through CY2020, almost all 87798 billing in large amounts occured in MolDx states. I also discuss this below, and include bar charts by year.

CMS has now released CY2021 data, on October 28, 2022. Total lab industry spending (including Anatomic Path) was about $8B before the main COVID codes, which added just about $1B more. Of this spending, $2B was in anatomic pathology.

Find 2021 data here:

https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Part-B-National-Summary-Data-File/Overview

Molecular Pathology Spending

By my best (though rapid) estimates, MoPath codes, including PLA codes and molecular microbiology, tallies about $2.8B before the main COVID codes. Add a billion for the main COVID codes, and mo path rises to about $3.8B.

For the rest of this analysis, I will leave off the main COVID codes, and work from the $2.8B number.

Unlisted Code is Biggest Code

The Unlisted MoPath code, 81479, rose to $409M, up from $290M the year before (up 40%).

At least in all past years, 95-98% of 81479 billing is in MolDx states.

- For example, Myriad MyRisk testing falls here under 81479, per MolDx coding instructions to Myriad.

- Increasing use of the 81479 code means that more and more of the Medicare molecular payment apparatus works separately from the statutory PAMA rate setting process.

- Increasing use of the 81479 code means it is impossible for outside researchers to know what genomic services Medicare patients are getting, making genomics unlike any other healthcare service (like "appendectomy" or "cardiac ultrasound" or "flu shot.") See next paragraph.

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP)

Public health experts interested in precision medicine would probably look to growth in the comprehensive genomic profiling codes, 81445, 81450, 81455. Use of these codes remained small. 81445, 5-50 solid tumor genes, with 2,505 uses at $1.5M (about $600 each). 81450, 5-50 hematopoietic cancer genes, with 16,040 uses at $12M (similar price). Finally, 81455, 51+ tumor genes, any cancer, with 4,310 uses at $12.4M (about $2900 each). The 4,310 uses of 81455 are dwarfed by, for example, 21,223 uses of Foundation Medicine 0037U, $74M, and likely similar usage of Caris comprehensive testing billed as 81479 under MolDx. In short, a health researcher looking only to 81445, 81450, 81455 which are the regular CPT codes, would see little of the actual use of CGP.

Proprietary Codes

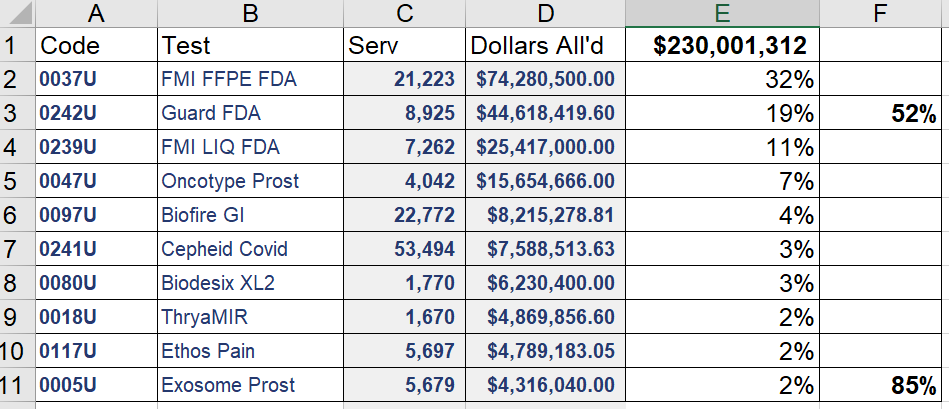

Leading proprietary codes are Cologuard at $253M (up 20%), Oncotype at $93M (up 20%), Foundation Medicine FDA (FFPE) $74M (down slight 4%). These 3 proprietary tests are 15% of all MoPath spending.

Highly Unlikely Codes (red)

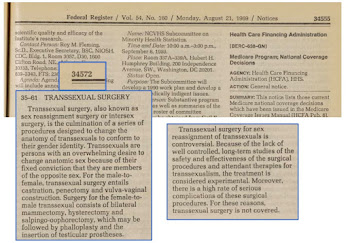

Before CY2018, when they were first assigned prices, Tier 2 codes were almost unknown in Medicare Part B billing.

Dollar volume shot up in 2018, 2019, 2020, even as DOJ was issuing press releasing that it was 'catching' bad actor labs, which, in data not mentioned by DOJ but discussed by me, the billing profile was Tier 2 billing, over and over again. And only in Novitas and FCSO states. Very, very, very little of spending for Tier 2 codes are labs like Ambry, GeneDx, Quest, etc. They can be labs with names like "ABC Lab" which by the time you hear of them, Google to be a small abandoned storefront in a mini-mall by a tattoo parlor.

Because of the years of attention, I was on the edge of my seat to see 2021 data. IT IS BAD. Tier 2 Level 9 rose from $207M in 2020 to $283M in 2021. That is, it got WORSE in the FOURTH year. Much worse. Adding often-dubious code 87798 (pathogen, other, PCR), about 30% of MoPath billing was at risk spending, to say the least.

This seriously distorts any analysis of overall growth (or medical needs imputed by usage profiles) for mopath spending in Medicare Part B.

See my videos about the scandal (overview here) and (one lab analyzed here). Press releases with CMS quotes talk about the dedication and tireless brilliance of the fraud detection efforts, but the stuff being done (by looking up billing records) is grossly obvious, can be shown in seconds in Excel, and you could train a 10 year old to recognize it in five minutes. And it's just the same in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 - there has been no evolution of the abusive and unbelievable billing patterns. And bizarrely, CMS pays for these Tier 2 genes in multiples as high as 5 (!!!), which is mind-blowing, if your mind isn't already blown to the ceiling.

Update: By November 2022, Novitas had put in belated billing article defenses against rampant Tier 2 code abuse - here.

Concentration

The top 5 codes had 44% of all spending, and 20% (about half) was gravely skeptical codes 81408, 87798. This is just plain crazy.

If some burocrat at CMS had just taken 5 god-dam minutes to change the MUE edit of 81408 from "2" to "1" (the NORMAL MUE number for genetics codes), it would have saved nearly $150M. (Assuming that took 5 minutes, it would amortize to saving about a billion dollars per hour of admin time.)

The top 20 codes had 72% of all mopath spending. The top 10 codes had 57%. Only 2 of the top codes were "PLA" codes, and both were FDA approved (0037U FMI FFPE, 0242U, G360 FDA).

PLA Codes

Of $2.8B in MoPath spending, only $230M went through PLA codes (or MAAA U codes). Of this, 85% went through the top 10 codes, and over 50% went through the top 2 codes (being Foundation FDA PPFE, and Guardant FDA G360). Only 75 of some 300 PLA codes were paid even $1000 by Part B. See the second chart below.

Screen Shots - Click to Enlarge

|

Top 20 Mopath Codes, 2021. (Red = Atypical, Green = Proprietary)

|

PLA only:My data as cloud spreadsheet

here.

Spending for Tier 2 codes, shown below, in bar chart from 2017 (baseline) through 2021. Total spending on 81408 was $283M, being almost identical in 2019 (year of "Operation Double Helix") and in 2021 (last year). (!!!!)

I've subtracted the baseline year, 2017, from 2018-2021 spending to get the 4 year excess spending on tier 2 of $857M. See excess spending bar chart below.

Almost no spending for 81408 went through NGS MAC or MolDx MACs; spending via Novitas MAC and FCSO MAC. Most labs billing 81408 billed it in multiples of 2 (occasionally, 4) - that's two full sequence of what the AMA defines as very rarely needed genes, per Medicare patient, one patient after the next.

Spending on 87798, Other pathogen, PCR. I've used 87799 (Other pathogen, quant PCR) as a control (see bar chart below).

At least through CY2020, labs billing 87798 were overwhelmingly in the MolDx states, with little usage in Novitas, FCSO, or NGS MACs. MolDx has since rewritten its pathogen reimbursement policy. Spending on 87798 in 2018-2021 was $537M, and if we subtract 2017 ($25M) as a baseline, excess spending on 87798 in 2018-2021 was

$437M. |

| 87798 2016-2021; 87799 as control |

|

| 87798 (for CY2020) by State (MolDx red) |

Are you keeping track? If excess spending for Tier 2 codes in 2018-2021 (over 2017) is $857M

and excess spending of 87798 in 2018-2021 (over 2017) is $437M,

that totals $1.3B.___

Notes.

The Genomic Health (Exact Sciences) prostate test (#5 on the PLA subsection at $16M) has since been sold to MDX Health,

here. The three major prostate prognostic panels for Cy2021 are Decipher at $37M (now Veracyte), Myriad at $29M, and Genomic (now MDx) at $16M. (I think the year before they were closer together).

I'm more than

dubious of

Noonan Syndrome 81442 being one of the highest-billed codes in Medicare genetics. This made no sense to genetic counselors I talked to, and volume on this likely-forgotten and unedited code rose from

$0 in 2019, to

$8M in 2020 (from a small number of little-known Southern labs) to

$35M in 2021. In 2020, half the volume was from one lab you've never heard of (not from Ambry's, or Quest's, etc). If a code skyrockets in use, and the code has no place in the Medicare population, and the code is billed only by labs with names like "ABC Lab" in Florida and Louisiana, it's a bad sign.

I think that cardiology genetics is potentially very important in the Medicare population, but knowing the status of coverage policies in CY2021, I'm not sure if the high billings of aortopathy panel, dup/del analysis, 81411, was from fully legit sources. Billing was $0 in 2019, $9M in 2020, and $48M in 2021, again from little-known labs and in a very few of the 50 states (FL, LA, TX).

That's right; in 2019/2020, Medicare paid out $100M for 81442/81411, which were paid $0 in 2019. Pretty big change in...standard of care. In Florida and Louisiana, at least.

COVID spending. Nearly all CMS COVID spending in 2021 went through high through codes U0003, U0004 ($75 each) and U0005 ($25 48 hour bonus). U0003 predominated over U0004 (8.7M vs 2.2M cases.) There were 10.9M cases of U0003/U0004 together, and most of them (9.2M, 84%) billed along with U0005 and got the $25 bonus. Dollars were U0003/4 at $818M and U0005 at $229M, or $1.05B.

Prostate MAAA tests. Prostate MAAA tests are led by Decipher 81542, Myriad 01541, Oncotype 0047U. These three collectively grew 47%, with group sales of $82M, but pulled farther apart from one another in 2021. Decipher grew 89% to $37M, Myriad 37% to $29M, and Oncotype only 5% to $16M.

Demographics. There's a database where you can get 2020 demographics by lab, I've listed demographics for Foundation Medicine as an example,

here.

Demographics of highly suspicious genetics labs. I checked one against a CMS provider-level demographic database (same as for Foundation in prior bullet). Genetic testing of pediatric genes for a population 14% over age 85, (!), 30% with Alzheimer's (!), getting exactly 12, individually ordered identical genetic tests each and every Medicare patient, and for diverse rare or pediatric diseases. Yeah, it would be hard for CMS detectives with years of experience, supercomputers and AI to find a hint of anything fishy here. (They were also 38% dual benes (poor), and 14% Black (racially balanced).)

Corrections made. Due to a sorting error, 81162 BRCA was omitted from the first edition, but corrected around 12N ET on 10/31. It should be the 5th highest code, and raises the total from $2.7B to $2.8B.